May 13 and April 10, 2023

Suddenly, our sailing season is over. As is the NIRVANA adventure—at least for me.

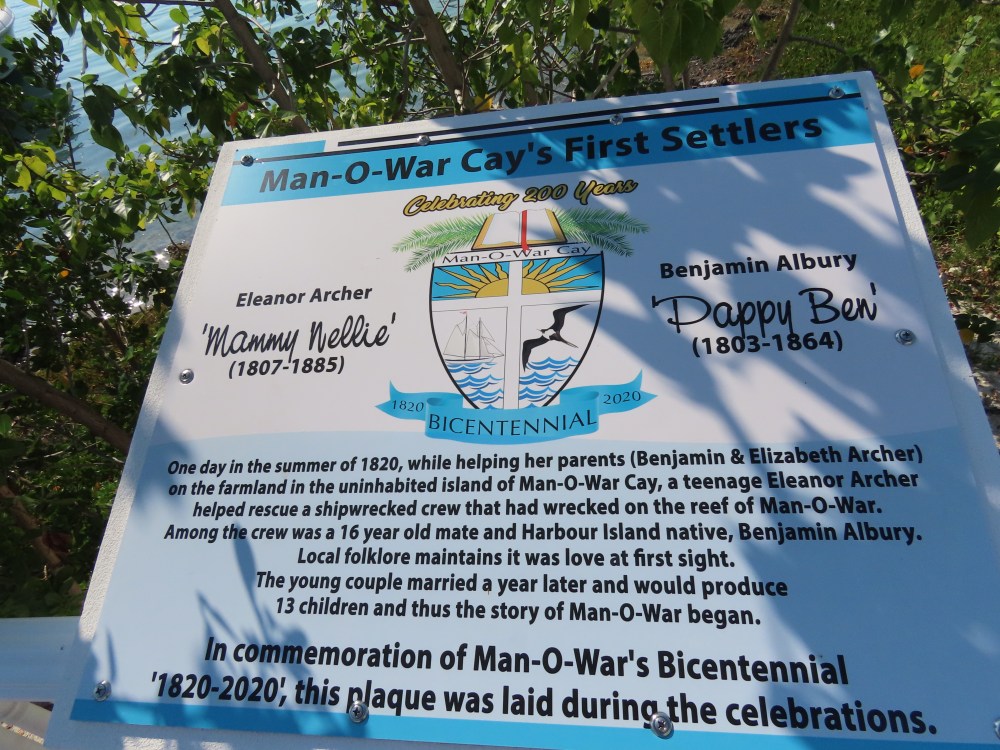

Will and I finished our three months of cruising in the Bahamas with two weeks in the Abacos, which included Little Harbor, Hope Town, Man-o-War Cay, and Green Turtle Cay. These were delightful islands but with a very different flavor, namely primarily white Bahamian islands that feel way more privileged and insular than most of the islands we visited. It’s astonishing how race, privilege, and class are so intertwined no matter where you go. That said, there is some fascinating history, most especially the rich boat building history on Man-o-War Cay, which has sadly almost disappeared. Also the presence of Hurricane Dorian, which devastated the Abacos in 2019, is still palpable.

Little Harbor

Hope Town

Man-o-War Cay

Mariah Maeve

We picked up our friend Sandy in Marsh Harbor for the last bit of cruising and the crossing to Florida. Thankfully, just before we left cell phone range, I learned about the birth of my granddaughter Mariah Maeve on April 6! At which point a pair of dolphins jumped across our bow welcoming her into the world. So suddenly I’m a grandmother as well.

The Crossing

The passage from Pensacola Cay to Fernandina Beach at the Florida-Georgia border was a whopping 330 miles and 53 hours: 70 miles across the Little Bahama Bank in relatively calm waters and 260 miles in open ocean. While the conditions were generally favorable, we experienced a little of everything—delightful sailing in fair winds and following seas with a full moon, demanding sailing in heavier winds and rolling seas, motoring in light wind and seriously rolling seas, a broken boom vang (again), and in the last two hours, wind and seas on the nose as the storm we planned to avoid approached. By all accounts, it was blissful, challenging, exhilarating, exhausting, and uncomfortable, in different measure, at different times, according to each of our experiences.

Transition Time

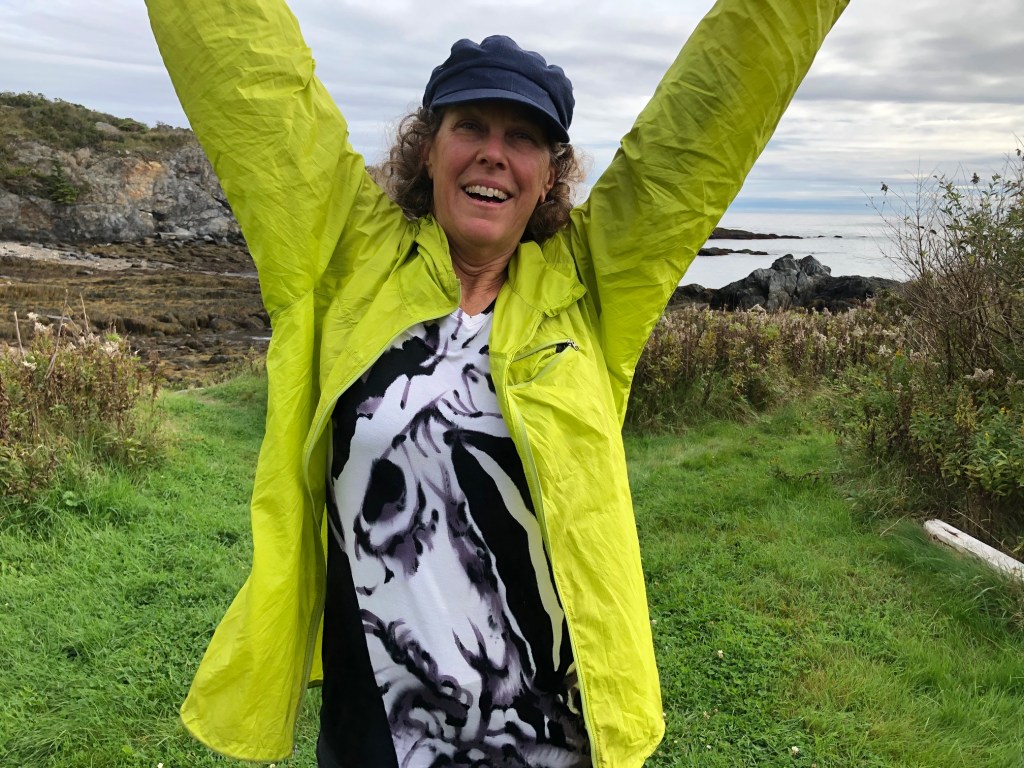

After our crossing, Sandy and I spent four nights ashore in a hotel while Will weathered a gale on a mooring as we awaited our flight back to Portland. Scrubbing off months of grime in a long, hot shower and sleeping in a large rectangular bed with crisp white sheets was nothing short of a miracle for this sailor. And time ashore in between the end of our trip and the return home was just what I needed to reflect, process, and write about our adventure together, which I do in more detail below.

Sadly, I returned to a house that was nothing like the way I left it when I rented it last fall. It took more than a week to clean, as well as to repair or replace what was damaged or missing. After two years of living mostly on the boat and renting my house, I am very happy to be home, where I’m reconnecting with my family, friends, and dance community and enjoying my own space.

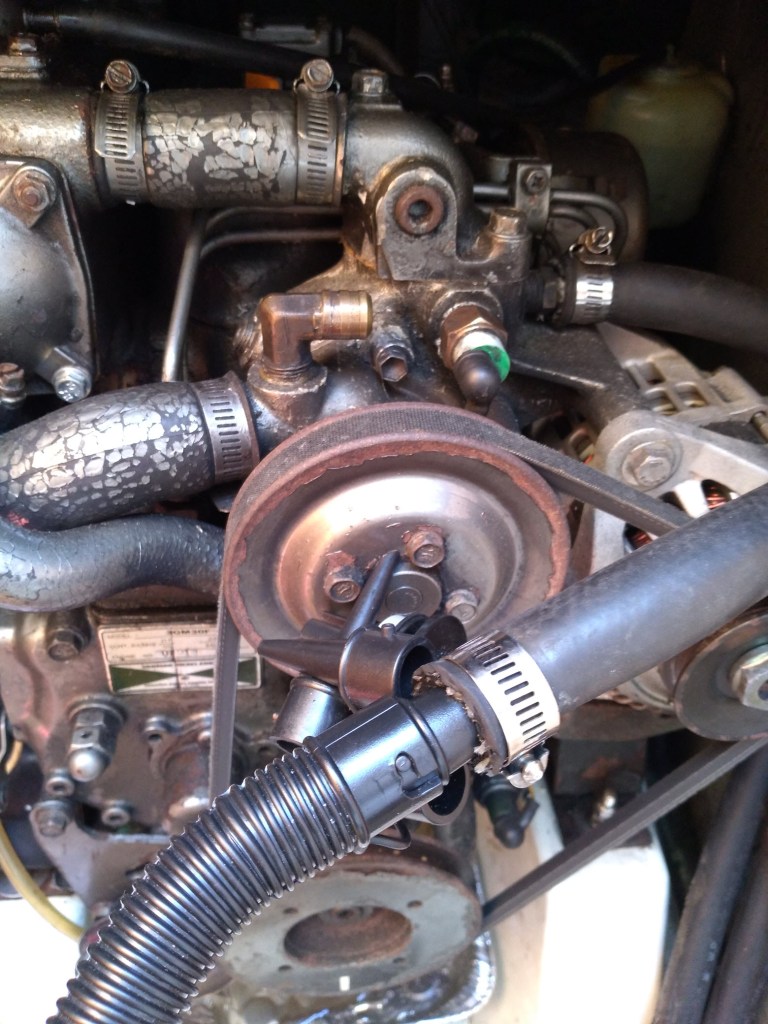

Meanwhile, Will flew back to Florida and began his trip sailing back to Maine with various crew joining him along the way, as well as doing some solo legs. Despite ongoing issues with the boat that have slowed him down, he continues to love everything about the sailing life, including sailing offshore in open ocean.

With time apart, we’ve both been doing some serious introspection about what our future holds. As such, I just returned from a quick two-day visit with Will in North Carolina. After much deep and rich communication, we’ve decided to close this chapter of our journey together living and sailing on Nirvana. While we have deep feelings for each other, we both acknowledge that our lives are moving in different directions. Will’s home is on the water, and my home is on the land. We are ready to open a new chapter with blank pages yet to be written—together and apart.

Reflection

And now for some deeper reflection on the overall adventure, which I wrote a month ago in Fernandina Beach.

I’m someone who likes to reflect on transitions. It helps me to understand the significance of my experiences: thus, this blog. While there does feel like a distinct before we left for Bahamas and an after we’ve arrived back “home,” in another sense, I know that life is one continuous journey.

My uncle Roland Barth, who passed away a year and a half ago and was a lifelong sailor, used to ask, “On a scale of one to ten, how was it?” I believe this self-inquiry can be a useful tool to help uncover a bit to what I’m talking about. But there’s also a danger in doing so in that it has the potential of flattening the experience, shaving the highs and lows into flat peaks and valleys. To honor my dear uncle, I still choose to answer the question I know he would have asked. My answer is a 7.5, which, given the range of feelings I’ve had over these months, is higher than I would have imagined.

Roland was also an educator, steeped in the world of experiential learning who, among other things, served for many years on the board of Hurricane Island Outward Bound. As such, the other question he would also ask is, “What were the lessons learned from your experience?” The answer to this question provides more meaning in helping move forward during these transitions. But here too a danger lurks in drawing too many conclusions about the future based on the past, for in reality, we are always in transition and the only real time is the present. So perhaps, as Rainer Maria Rilke suggests, it’s more about asking the questions and swimming around in the soup of what comes up that insight comes.

Finding Home

What’s it all about, this life aboard a floating home? I’ve been asking myself this question for going on two years now. Since June, 2021, we’ve been living aboard sv Nirvana or sv Cascade in Italy, with only a few months’ break on land last spring when we house-sat for a friend and traveled out west. It’s what my grandmother would call a “peripatetic” life—one of her favorite words—which means moving from place to place.

So what does this say about “home?” Will, the architect, often paraphrases Gaston Bachelard from The Poetics of Space about the significance of the word home: “Home is a place that shelters daydreaming.” In other words, home is a safe place from which to explore…and presumably return. Yet when you’re living and traveling on a boat, you’re constantly exploring and, thus, daydreaming is not about dreaming at all but about living in constant flow. As for returning, there is instead a continual exploration from what is essentially home, so it’s both the safe haven and the journey all rolled into one.

Living on a boat is truly a different way of moving in the world.

The contrast between the stability of life on land—a house, say—and the motion at sea is profound. Literally, the boat is constantly moving, whether sailing at six knots or drifting around at anchor as the wind changes direction. The seas are rarely flat, so there’s an ongoing forward-and-back or side-to-side motion, or both. Sometimes the movement is gentle like being rocked in a cradle; other times it’s like being on a combination mini-roller coaster/tilt-o-whirl perpetual motion machine. And everything in between. On the rare occasion that you’re anchored in a totally protected harbor and there’s no motion at all, you notice it: “Oh right, this is what it feels like to be on land.”

To assemble meals, you pull food from a deep refrigerator or from behind cushions that serve as a couch, both of which can involve an archaeological dig. To use the toilet, you step into a space that doubles as a shower. The water is only hot when you’ve run the engine, or barring that, you hang a solar bag or use a hose in the cockpit. The water supply is limited to 60 gallons, plus what you can make with the water-maker, so you use it sparingly. And you constantly monitor your batteries to ensure the solar panels are feeding enough power to keep up with your electrical use, which is generally minimal.

It’s micro-house, off-the-grid living on the water.

What this way of life affords is the ability to experience and explore in ways that are simply not possible on land. As such, contact with the human-made land world has a much greater impact as it’s no longer the norm but more the exception. While the boat is, to be sure, a human-made object that requires constant care and attention, the sea and sky are just outside the companionway, laid out before you in a splendid expanse, meeting at the horizon. From this perspective, land is as close or as distant as you choose to make it.

There is something truly elegant and appealing about the efficient living space, small carbon footprint, and preservation of precious resources that boat life provides. And yet, after these many months, I’ve discovered I need more time on land to counteract time on the boat: walks ashore in the greenery of nature; buildings that shelter the elements; a soft, cozy chair in a room with a tall ceiling; a rectangular bed; a shower where the hot water washes over you in a constant flow; a flushing toilet. Call it the creature comforts, stability, and spaciousness of a land-based existence, which are fleeting on a boat where the only buffer between you and the elements is a fiberglass hull and a canvas dodger.

Still, when the sun penetrates your bare skin, continual breezes caress your body, warm water buoys your entire being, and wind fills your sails on a perfect reach, you feel held in the embrace of both your boat and nature in a state of true bliss that simply cannot be replicated on land.

Lesson Learned: Take some time in life to push the edges of your comfort zone and adventure out from the safe harbor of home. Only then will you discover the true meaning of home for you.

Responsibility

Here’s a different take on the word “responsibility”: the ability to respond to what’s happening in the moment.

Life on a boat is an exercise in constant responsiveness to the environment, which begins with the weather and sea conditions and extends to every other aspect of life that exists. The universe is constantly changing; so is the weather, your surroundings, the people you come in contact with, and your feelings. Just when you think you’ve found the perfect settled anchorage, a new weather pattern develops. At the intersection of the high- and low-pressure systems is weather instability, higher winds, bigger seas, perhaps rain.

At a calm anchorage, when the sun is shining down and a gentle breeze is blowing, you can become lulled into a sense of complacency as if it could go on forever. But this is simply not so. The weather is a complex, dynamic system that is only predictable to an extent. For what in the universe is fully predictable? At the sub-atomic particle level, Heisenberg introduced the Uncertainty Principle in 1927, which states that you can know when a particle will be at a certain location with 100% certainty or you can know where it is right now with 100% certainty, but you cannot know both at the same time. This is the current state of our knowledge about the time and space: despite our best efforts, it’s not entirely knowable or predictable by humans. That goes for subatomic particles, stars and planets, evolution, the weather, the economy, the fickle minds and hearts of humans—indeed, the universe.

As just one example, given the state of today’s technology and how it has infiltrated the world of sailing, it’s sometimes hard to remember this simple fact. As we devote ourselves to weather apps, plot courses on electronic charts that we believe to be accurate, and focus on wind, speed, and GPS signals as the boat bounds through the waves, we are seduced into thinking we can—or at least should be able to know or predict what’s next. This is a far cry from sailors of the past who determined their location using celestial navigation and “knots” tied onto ropes that they tossed over the bow and then counted at the stern to determine boat speed. Not to mention sailing in uncharted waters!

Part of sailing is not only accepting but embracing that despite our best efforts at control, we are in fact always in the flow. The crossing from the Bahamas to Fernandina Beach is a case in point—a true practice in response-ability. For me, sailing is and has always been a practice of dancing between surrender and control, with my comfort zone being more toward the control end of the spectrum. While I’m quite nimble at the helm and have excellent instincts when it comes to all things related to sailing, the unpredictability of the environment has been stressful for me. Will, on the other hand, has fully embraced living in flow on the boat, loving every minute of it, no matter what arises.

Lesson Learned: Accept that life is fundamentally unknown, try not to project too much into the future, and respond to what arises in each moment with grace, agility, intelligence, and heart. Plan when planning is required, but try not to have too many expectations for how it will turn out.

Relationship

For the past almost two years, we’ve been together in a small space virtually 24/7. So at the same time that we’re navigating the wind and waters, we’re navigating our relationship.

Life aboard a sailboat with a partner is an example of what my uncle used to call “relentless intimacy.” To address this, he wrote a book called Cruising Rules, a tongue-in-cheek account of how to navigate human relationships aboard a boat. The only cruising rule Will and I adhered to is that we “share the helm,” which means whomever is at the wheel gets to decide how we sail. We can and often do bounce ideas or suggestions off each other, which the captain-of-the-moment can choose whether or not to accept. That said, over time, we’ve become quite specialized in our roles. For the most part, we make a good team, although we definitely have our differences in sailing style. Accepting and appreciating those differences has been an ongoing practice.

While I tend toward planning, organization, and broad awareness, Will tends toward being in the moment, sensing the feel of the boat, and doing what needs to be done when the need arises. These differences are often complementary and can have a balancing effect on each of us. I notice when things need attention on the boat, and he’s happy to fix them. He notices when I spend too much time plotting courses, and I let go of some control. I organize and stow things in logical places, and he is coming to appreciate that this approach is helpful for finding things.

Over these many months, my emotional barometer has fluctuated between steady and rising slowly (appreciation), steady and rising rapidly (enthusiasm), steady and falling slowly (apprehension), and steady and falling rapidly (depression). A high can linger without a cloud in the sky, while at other times, lows float in unexpectedly on the wind. Will’s barometer, on the other hand, is steady and high most of the time, regardless of wind, waves, weather, or the state of various pieces of equipment on the boat that need attention.

Lesson Learned: In any relationship, accept the differences between you, be honest about your thoughts and feelings, and navigate the level of intimacy according to your own needs and desires.

* * *

I’ve come to many of these realizations late in life and not without some serious intention. Thus, the title of this blog—surrender to the abundance—is a practice and aspiration for me.

And yet, I’ve noticed that when I’m truly honest with myself and others, and when I let go of control and expectations, that’s when the universe provides in unexpected ways. Like stating out loud that I needed a break from the boat and being invited to stay with Sylvia and Elza on Cat Island. I hope that by the time I lay my head to rest at the end of the day, literally and figuratively, I will have surrendered fully to the abundance that surrounds us all at every moment.